The internet is not the place we once knew. Every week, millions of people argue with AI bot networks and paid workers at troll farms like the Internet Research Agency, a Russian organization based in St. Petersburg, which became known for state-sponsored online influence campaigns targeting the United States and Europe. At its peak, the IRA had 300–400 employees working in shifts, generating tens of thousands of posts per month with a $1 million per month budget. During high-profile events in the 2010s, up to one in three interactions on social media were inauthentic — now, with the help of AI, it’s exponentially more.

In recent years, an older fringe theory has re-entered the conversation — the Dead Internet Theory. It claims that most of the internet’s content and interactions are no longer produced by real humans but by bots, AI-generated media, and algorithmically boosted noise. Central to the theory is the belief that platforms, governments, or corporations are complicit in this artificialization, either by design or for profit.

At face value, it sounds conspiratorial, but underneath that claim is a darker truth. We are increasingly navigating a digital world where authenticity is manufactured. With the rise of generative AI, it’s become cheaper and faster to produce misinformation. While Dead Internet Theory points to a real and growing distortion in how people experience the web, it is now supported by journalism, cybersecurity research, and academic work. The result is a feedback loop of performative virality, where trends are driven less by real interest and more by engineered momentum.

All the research papers and leaked documents used for this article can be downloaded from our XDA Mega Drive. Special thanks to Benn Jordan for his video and the research he provided.

Related

Pinokio makes installing ComfyUI a breeze

Pinokio lowers the barrier of entry for beginners

The internet isn’t dead — it’s distorted

A fringe theory finds new relevance

Source: Agora Road Forum

Dead Internet Theory argues that since around 2016 or 2017, the internet has become increasingly synthetic — populated by artificial personas, auto-generated articles, and automated engagement — while genuine human activity is drowned out. The theory traces back to message board discussions on 4chan and Wizardchan, and gained broader attention after a 2021 forum post on Agora Road by a user named IlluminatiPirate. A year later, ChatGPT was released to the public, and journalists began revisiting the theory.

In January 2024, Dani Di Placido, a senior contributor at Forbes, published a piece explaining Dead Internet Theory — and completely missed the point.

“There are bots out there, sure, but the theory does not describe the internet of today, let alone in 2021. Social media sites have always taken measures to block spambots and still do, even as the bots are evolving, aided by generative AI.

At the moment, generative AI is not capable of creating good content by itself, simply because AI cannot understand context. The vast majority of posts that go viral—unhinged opinions, witticisms, astute observations, reframing of the familiar in a new context — are not AI-generated.”

While estimates are sometimes higher, at least 40-50% of the accessible internet is reportedly fake. And honestly, I doubt you need convincing that less than half of what’s online is reliable — nearly every major research study backs up what most people already know from experience. Internet freedom is at an all-time low, and advances in AI are making things much worse.

Di Placido and many other mainstream journalists fail to recognize that generative AI doesn’t act independently. There’s always a human behind it, using it intentionally. The issue isn’t whether AI can produce good content unassisted — it’s how it’s used to manufacture engagement at scale, distort visibility, and flood platforms with synthetic influence and supercharged online disinformation campaigns.

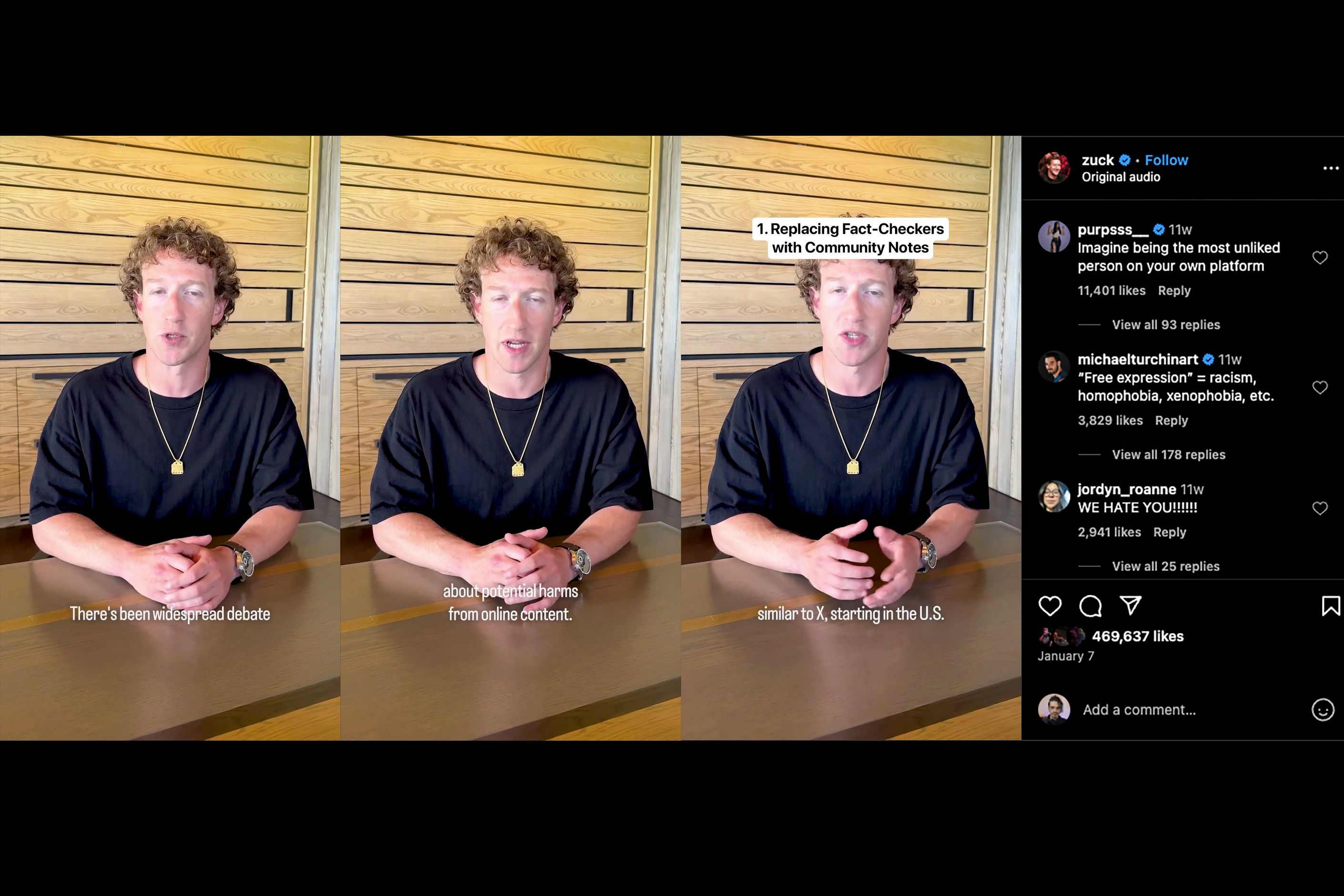

Source: Instagram

As for the idea that social media companies are actively fighting this, come on. These platforms profit from inauthenticity. It’s built into how they work. Zuckerberg literally announced Meta would end fact-checking across all its platforms. Musk shut down Twitter’s entire election integrity team in 2023, then months later launched a so-called Election Integrity Community — a 50,000-member group flooded with conspiracy theories about voter fraud and ballot tampering.

And we know where Musk’s support for Trump took him — giving a Nazi salute on stage, interfering in U.S. and German politics, positioning himself as an unelected cabinet member through Doge, tanking Tesla’s value, and becoming one of the most hated people on the planet. So no, it’s not far-fetched to think he’d actively shape the platform to reflect the same manufactured reality that the Dead Internet Theory describes.

The illusion of engagement

Scalable propaganda overwhelms organic speech

Source: Myspace

When I refer to bots, I mean the full spectrum of inauthentic content — AI-generated personas, troll farm workers, fake followers, mass-produced replies — anything designed to simulate real human engagement without actually being it. If the internet feels fake lately, you’re not wrong — and it’s not just politics. Bots are flooding every major event, from elections to pop culture, war coverage to brand promotions.

This new generation of AI botnets doesn’t just mimic participation; they outperform it. They’re fast, tireless, and built to game algorithms that reward activity over authenticity. What trends aren’t what people value — it’s what provokes the most reaction. Rage bait hits harder, spikes dopamine, and keeps people coming back for more.

The shift away from organic content didn’t happen all at once, but for me, it was clear when MySpace forced that redesign in 2010. The site used to let you shape your own space — custom code, music, your actual interests — and suddenly it all got flattened into a generic profile nobody asked for. That was when people started leaving, and I don’t blame them.

What stuck with me wasn’t the interface—it was what it said about where things were going. We went from customization to uniformity, from expression to performance, from conversation to feed.

Related

Best AI applications: Tools that you can run on Windows, macOS, or Linux

If you want to play with some AI tools on your computer, then you can use some of these AI tools to do just that.

In those early years, the internet felt like a way out. It was where people shared real experiences — music, stories, ideas, pain, humor — and for someone stuck in a small town, that meant everything. I built networks that helped me tour as a musician, meet thousands of people, and make friends I’m still close to today. Whether it was good or bad, it felt like you were actually connecting with other human beings.

There were jerks, of course — some just stirring things up for fun, others just bitter and toxic — but it never felt fake. It felt like people being rude, not some corporate operation. That’s what’s different now. What used to be one person causing chaos has scaled into something else entirely. It’s faster, more coordinated, and often not even human. And it’s not just about trolling anymore — it’s about controlling the narrative.

Who’s behind the bot swarm?

State-sponsored manipulation and psychological warfare

Source: Wiki Commons – Buaidh

The information war we’re living through didn’t start with social media — it’s the modern form of something that’s been developing for decades. Propaganda was already a battlefield in World War II and the Cold War, and psychological operations have long been part of military and intelligence strategy. But the shift we’re seeing now — where disinformation is constant, scalable, and interactive — can be traced directly to Russia’s experiments in the 2000s.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia faced economic disaster, social unrest, and plummeting global influence. The Kremlin responded by investing in narrative control. One of the architects of this effort was Vladislav Surkov, an adviser to Vladimir Putin, who openly supported contradictory propaganda, intentional confusion, and information chaos as tools of governance. This wasn’t about making people believe a single truth — it was about destabilizing the very idea of truth.

That approach took form through the Internet Research Agency, which became a model for industrializing disinformation. Their workers weren’t just trolls — they followed quotas, used internal style guides, and operated fake personas across ideological lines to inflame division and erode trust. Some posed as hardline conservatives, others as Black Lives Matter activists. The chaos was deliberate.

U.S. intelligence agencies confirmed their involvement in the 2016 election. But the larger goal was never just electoral — it was long-term destabilization. Push enough noise into the system, and the system starts to fail. People stop believing in facts, in institutions, in each other. Troll farms reached 140 million Americans a month on Facebook before the 2020 election.

Other nations followed the same playbook. Today, over 70 governments — including China, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Israel, India, Venezuela, and even the U.S. — run organized disinformation programs. Whether run through AI-generated personas, troll farms, or covert amplification networks, the strategy is the same: turn division into a weapon and let the public do the rest.

Despite mounting evidence that digital warfare is escalating, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth has halted all offensive cyber operations targeting Russia. The move is part of a broader rollback of U.S. initiatives to address online threats — from disbanding election security teams to scaling back federal investments in cyber defense. With fewer countermeasures in place, the volume and sophistication of disinformation will only increase. More of what we see online will be fabricated, and we’ll be left to navigate it with even less protection.

Related

Adobe Photoshop’s Firefly vs. ComfyUI and Stable Diffusion

There’s an extremely powerful and free tool that shouldn’t be dismissed

Domestic manipulation by influencers and corporate interests

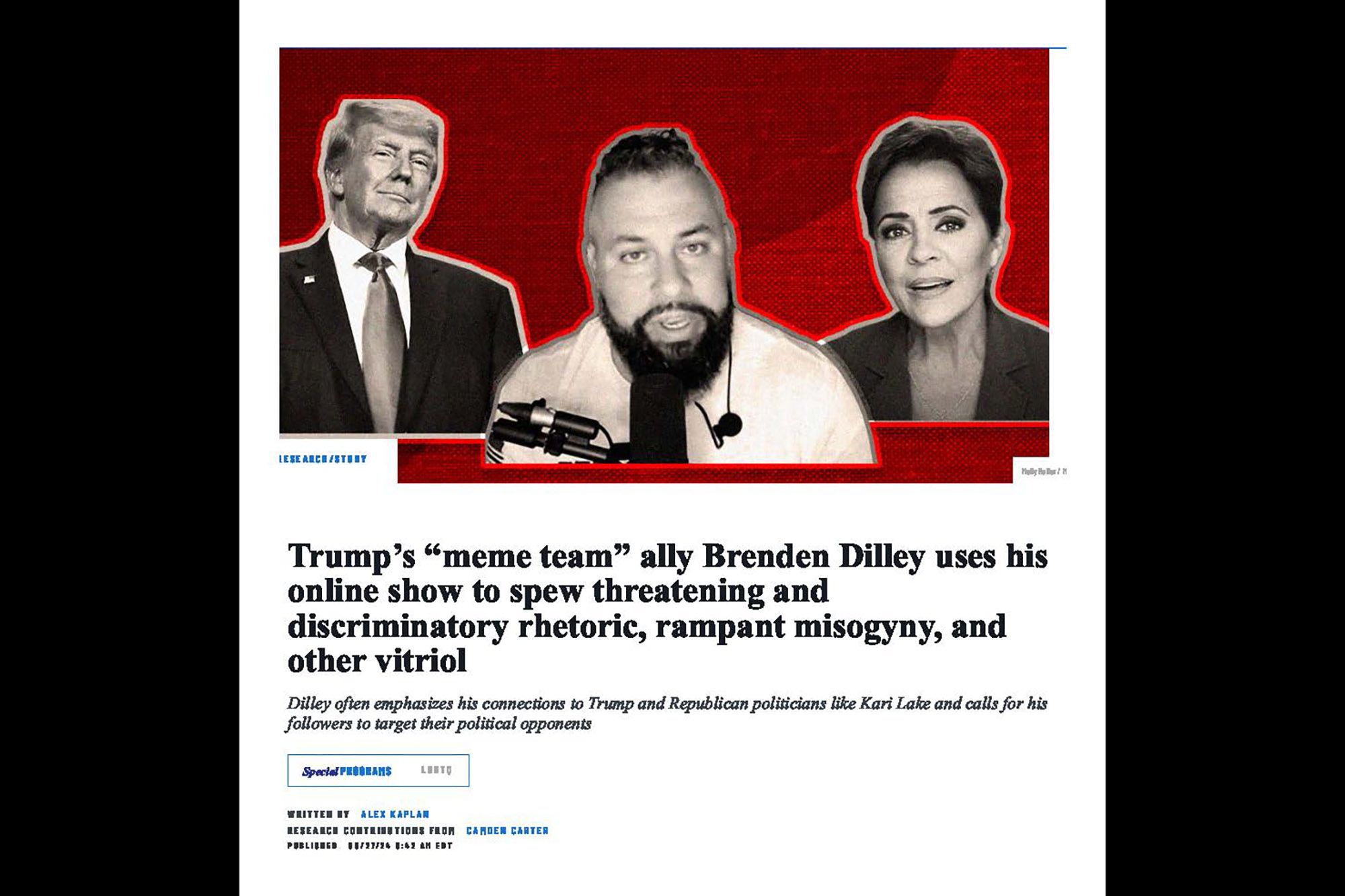

Source: Media Matters

Coordinated disinformation isn’t limited to state actors. Influencers, political figures, and corporate interests routinely use similar methods to shape public perception. The difference is in motivation, not mechanics.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal exposed how personal data could be harvested and used to build psychological profiles, enabling targeted political messaging optimized for emotional response. That model — micro-targeted content designed to influence behavior — was not just effective; it became standard practice across political and commercial domains.

Since then, domestic actors have expanded these tactics. Brands and reputation firms deploy bots to flood posts with supportive comments or to drown out criticism. Influencers buy likes, shares, and comments to inflate their metrics and qualify for sponsorship deals. Coordinated campaigns simulate popularity, suppress dissent, and seed narratives across platforms. Much of this engagement is automated or outsourced, and few disclosures differentiate authentic user responses from synthetic amplification.

Recent investigations confirm that bot-driven promotion extends to extremist political content. In 2024 and 2025, reports identified coordinated efforts to amplify right-wing influencers tied to election denialism and foreign propaganda, including operations linked to Russia. These accounts received high volumes of inauthentic engagement, distorting both reach and perceived legitimacy. Once a post attracts enough interaction — real or fake — it gains algorithmic momentum and wider visibility, reinforcing its influence.

Platform incentives further reinforce the issue. Twitter removed core moderation systems, allowed paid verification to enhance algorithmic reach, and permitted bot networks to manipulate trending content. Internal safeguards against coordinated inauthentic behavior were reduced or eliminated, enabling sustained visibility for known disinformation actors. Attempts to counter these narratives often received less traction or were throttled by design.

The infrastructure favors interaction over accuracy and reach over reliability. Disinformation thrives not because it is persuasive, but because the systems are built to reward engagement regardless of its source. That structure mirrors the core premise of Dead Internet Theory — not that the internet is literally dead, but that synthetic signals have eclipsed authentic human interaction. On social media, those distortions are no longer theoretical — they’re measurable, monetized, and widespread.

Recognizing digital disinformation systems

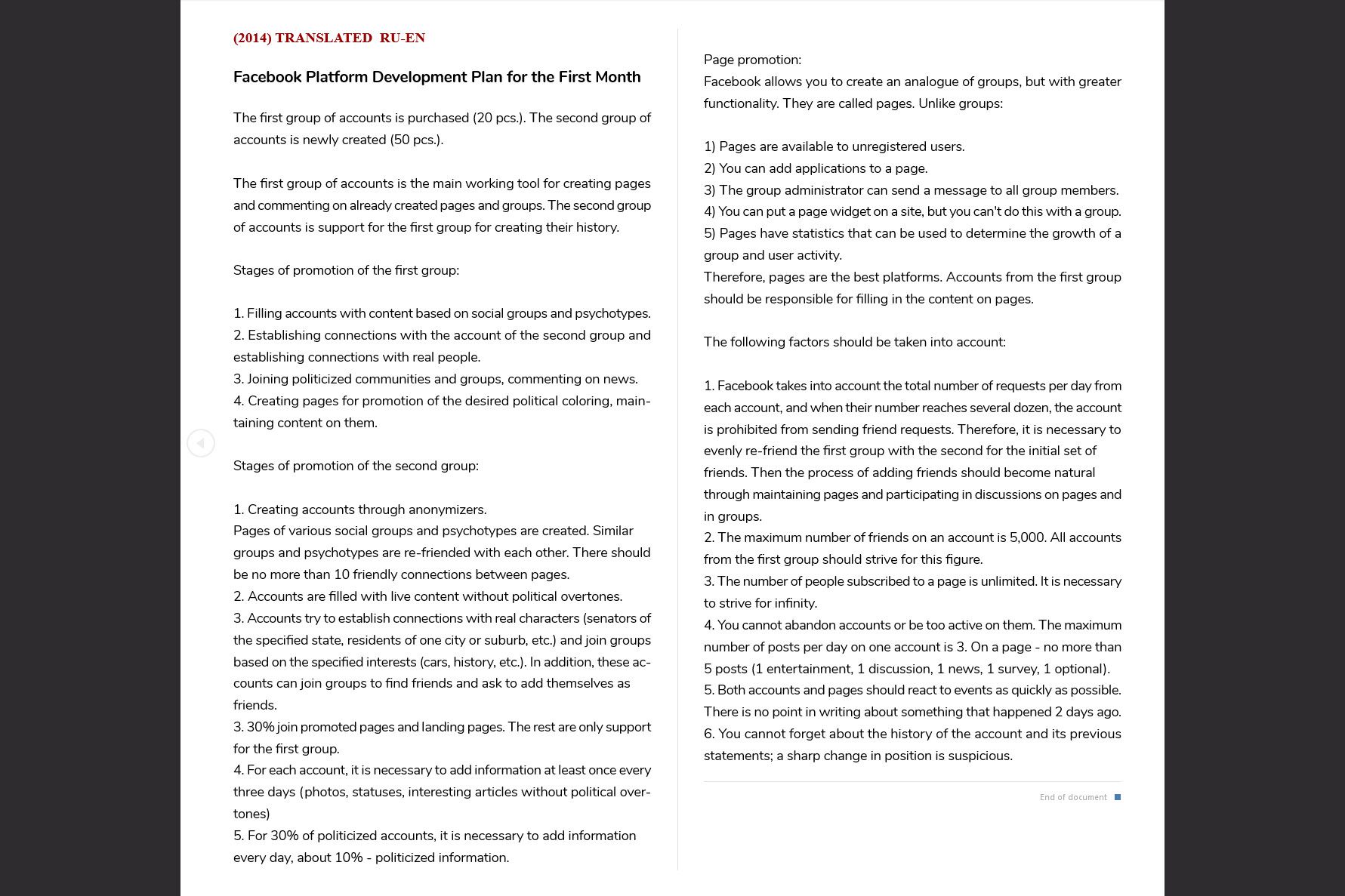

How modern troll farms build disinformation at scale

Troll farms recruit workers through vague data entry job listings. After signing NDAs, new hires are informed that their actual task is to impersonate Americans or citizens of the target country. Each worker manages multiple fake personas across platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Telegram. They are given scripted biographies, curated photo albums, and politically aligned content libraries. A single operator might run ten or more personas simultaneously, each with its own name, backstory, regional dialect, and ideological slant.

The structure is systematic. Workers operate in rotating shifts under the supervision of team leads who assign daily topics, review performance, and enforce strict engagement quotas. The worker is warned or replaced if a persona fails to generate enough replies, likes, or shares. Workers post memes, arguments, viral clips, and emotional bait, often drawn from pre-approved archives. Increasingly, farms use AI-generated content as a base, lightly edited to match tone or persona traits.

Source: Benn Jordan

Leaked operational manuals from the IRA and similar operations instruct workers to maintain plausible behavior. They’re told to post non-political content every few days — personal stories, local headlines, photos of pets or food — to blend in with authentic users. Persona accounts are expected to join community groups, follow politicians and businesses, and engage with trending topics. There are specific protocols for when to comment, when to react, and how to escalate posts to appear viral.

Workers are often tasked with playing multiple sides of an issue. Using opposing personas, they stage heated arguments in comment sections to draw in real users. These exchanges are designed not to persuade but to disrupt, amplifying confusion, outrage, or tribalism. Some accounts push conspiracy theories, while others fact-check them. The goal is to erode trust and blur consensus, not build it.

Modern troll and bot farms resemble digital marketing firms. They use performance dashboards, content calendars, quota tracking, and style guides. Some teams focus on disinformation seeding, and others boost engagement to create the illusion of consensus. Like campaigns, they execute in cycles, targeting specific issues, demographics, or elections. What appears as organic debate is often manufactured one post, shift, and script at a time.

How to recognize inauthentic content — and stop feeding it

Most people don’t need academic tools to spot a fake account — they just need to pay attention. If a post triggers an immediate emotional response, pause. Troll farms and bot networks rely on manufactured outrage to redirect your attention toward division. That’s the product: not the post, but your reaction.

If you’re unsure and feel compelled to find out, click through the poster’s profile. You don’t need to investigate — just glance. Look at the name, the profile picture, and the bio. Fake accounts often follow trends. One week it’s vector art avatars, the next it’s photos with dramatic lighting and vague, motivational taglines. They might use similar naming structures or lack any specific personal info. Real people are inconsistent. Bots follow templates.

Thumbnail patterns are another easy giveaway, especially on platforms like TikTok or Instagram. Real people’s profiles usually reflect their lives — faces, places, events, and random hobbies. Bot accounts often display rows of thumbnails with nearly identical styling: same fonts, same poses, same topics, repeated endlessly across dozens or hundreds of accounts. If you notice that, you’re not imagining it.

Language gives them away, too. Some bots use emotionally loaded hashtags and phrases like bait; others try to sound calm and “rational” while quietly spreading disinformation. Either way, the giveaway is repetition. If a comment looks like the same dozen others you’ve seen, that’s because it is. Bots copy from a script because scripts work.

- Pause if it makes you mad — strong emotions are a red flag.

- Click the profile — real people have randomness: friends, photos, quirks.

- Scan for patterns — look for repetitive names, bios, or thumbnails.

- Trust the vibe — if it feels staged or scripted, it probably is.

- Limit your replies — if you’ve already gone back and forth once or twice, don’t get pulled into a loop.

The simplest rule? If something feels off, don’t engage. If a post reads like it was generated, or the account seems oddly polished and hollow, it probably is. And if you just can’t help yourself, don’t argue — just leave a comment that says, “I checked. This is a bot.” You’ve already done the legwork. If you’ve already gone a few rounds in a toxic back-and-forth, that’s your cue to stop. Every reply feeds the system, so keep the engagement to a minimum and move on.

Related

How to build basic workflows in ComfyUI

ComfyUI is an incredibly powerful tool for anyone aiming to stay ahead of the AI curve.

The internet has not died, but it has been occupied

The internet today reflects a shift in control — away from people, and toward systems engineered to manipulate attention. Disinformation is no longer just a tactic. It’s an industry. Coordinated botnets, AI-driven personas, and engagement-optimized algorithms have built a reality that rewards outrage, buries truth, and distorts what’s real.

These aren’t abstract problems. They appear in your feed, conversations, and sense of what’s popular or true. And while it’s easy to feel outnumbered, the signs of manipulation are visible — if you know what to look for: repetition, emotional bait, generic accounts with inflated visibility. Most people already sense something is off. They just haven’t been told what to do about it.

A new generation of platforms is emerging — decentralized, user-governed, and designed to resist the failures of legacy networks. Mastodon and Bluesky (Twitter), Pixelfed (Instagram), PeerTube (YouTube), and Skylight Social (TikTok) are built on open protocols that give users real ownership over what they see and share. Moderation is transparent and community-driven, not dictated by opaque systems. Bots face real friction through shared blocklists and public oversight. These aren’t just alternatives — they’re structural rewrites of social media itself, with privacy, autonomy, and integrity at the core.

There is no reset button. But there is a way forward. We must become active participants in shaping our digital environments rather than passive consumers of curated illusions.